“I’m finding it hard to judge timings in my lessons. It’s really hard to predict how long things will take and I’m still getting it wrong… it makes me panic mid-lesson!”

Daniel, English trainee teacher

The effective use of lesson time is a skill evidenced in Standard 4, and it’s important to make it a priority this year. Research by Anders Ericsson, a professor of psychology at Florida State University, formed the basis of Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers: The Story of Success (2008), which claimed that it takes about 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery in a certain skill. Although there has been lots of debate since then about the validity of that number, it is still important to remember that you cannot master the art of planning lessons in your initial teacher training year. But what you can do, and absolutely should do, is get some of those hours in the bank now!

I train my teachers to understand the difference between two techniques I call ‘micro planning’ and ‘macro planning’.

Micro planning

It’s very tempting early on in your career to start with the little details and work outwards. Typically, a trainee will start their planning at the first five minutes of the lesson and immediately jump to the starter activity.

What do I want my students to do when they enter the classroom? This is often the first question training teachers ask. From that starting point, they will build a solo lesson minute-by-minute and spend hours scouring the internet for resources. It becomes more about the resource and finding the right picture for the PowerPoint than it does about the actual learning.

If you’re doing this, then it may be the reason why you’re struggling to manage time in the lesson.

Macro planning

This technique forces you to think about the learning journey as opposed to staccato one-off events in your planner. You begin by zooming right out and looking at the bigger picture in the topic. Think:

-

What knowledge do I want my students to have by the end of this sequence of lessons?

-

What skills do I want them to be able to demonstrate at the end?

If you think like this, then work backwards, the resources almost become irrelevant. They’re just ‘add ons’ at the end.

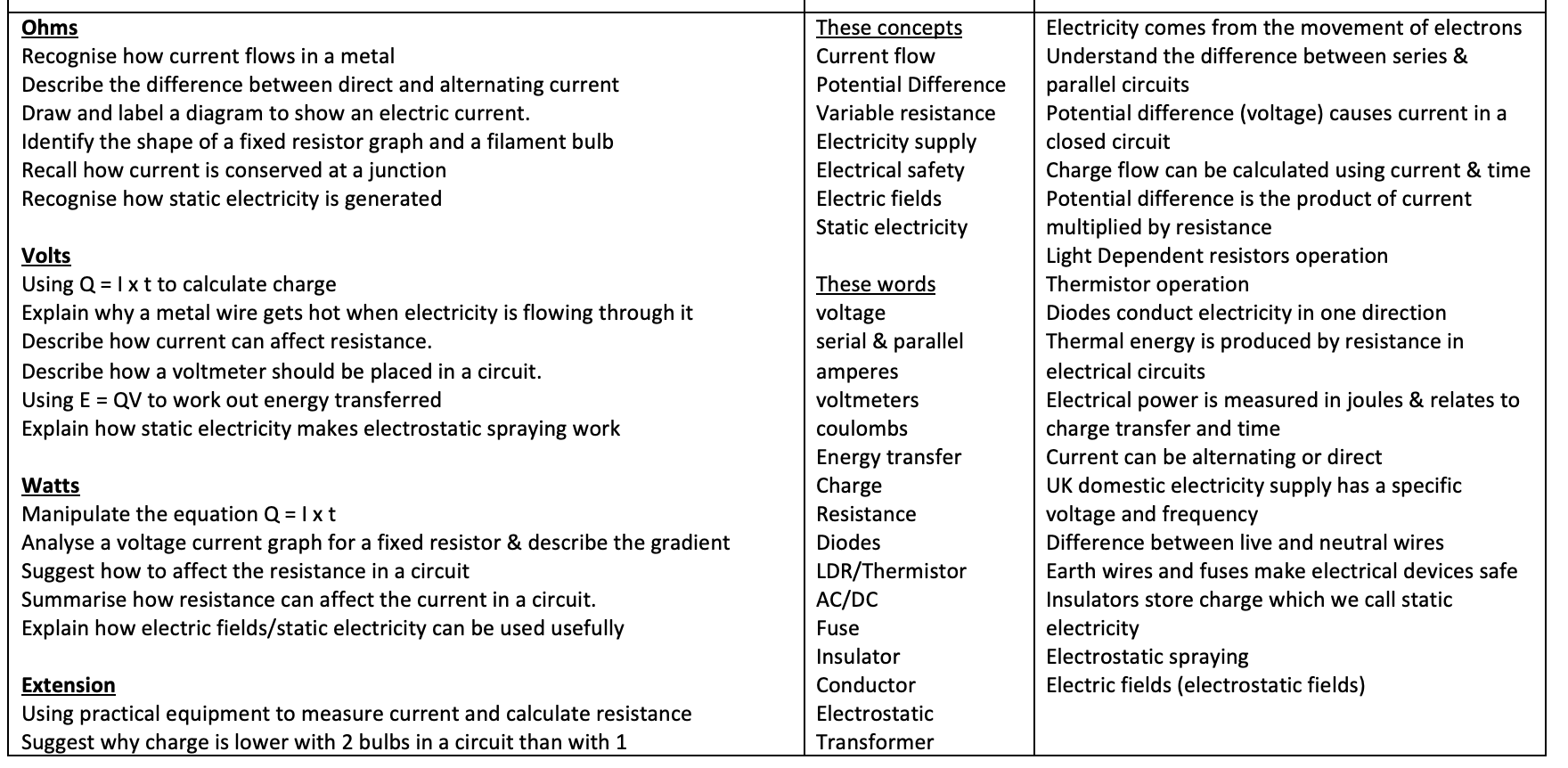

You'll find an example of a macro plan for a physics topic, kindly donated by one of my trainees above.

-

The first column summarises what students will be able to do (the skills).

-

The final column captures the important ideas they will encounter (the knowledge).

-

The middle column focuses on the topic’s key concepts and language.

If you macro plan like this first, it will give you a much better ‘map’ of where you’re taking your young minds. From this point, plan lessons in chunks with the learning outcomes/objectives in the first column. Forget about time and plan for knowledge and skill acquisition instead. It’s worth remembering that one class may take three lessons to secure their understanding of a key concept, whereas another class might only take one. If you know where you’re going on the big journey and you have it mapped out, then you will never have those moments of panic in a lesson when your activity timings are off, because you will know what’s coming next.

Just remember that successfully mastering Standard 4 will have the biggest impact on students’ progression.

Reference

Gladwell, M. (2008) Outliers: The Story of Success. London: Penguin Books.

An example of macro planning.