Until the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, which led to the tearing down of his statue by protesters, you could not visit Bristol without coming into contact with a memorial, school, road, or building named after the city’s now infamous son, Edward Colston, who ploughed a fortune into the civic and philanthropic life of the city. Bristol Council had previously suggested an additional, and highly controversial, plaque for his city centre monument, which referenced his role in slavery:

Edward Colston played an active role in the enslavement of over 84,000 Africans… and as a Tory MP for Bristol (1710-1713), he defended the city's 'right' to trade in enslaved Africans.

Public consciousness has changed profoundly as a result of the BLM campaign, and we are starting to hold historical figures to account for their role in the darker side of British history, and how the development of the West is understood.

Colston is hardly alone as someone who made a fortune from the brutality towards African people. Enslaved Africans were shipped to the Caribbean and Americans; the goods they produced sent to Europe for manufacture and; in the final stage of the vicious triangle the ships were sent with goods, shackles and guns back to Africa to procure more of the enslaved. Bristol was one of the most important ports in the slave trade in Europe and owes its place in the world to the profits it reaped. The most uncomfortable aspect of the Colston story is that as one of the most successful in that trade it makes perfect sense that he would be lauded as a hero of the city. Whilst it may seem obvious that publicly celebrating the achievements of a slave trader should be avoided, the truth is that without people like Colston, maximising their wealth off the horrors of slavery, Bristol (and the wider UK) would simply not exist as they do in the same way. This is why is it is so difficult (perhaps impossible) to honestly reconcile the horrors of the colonial past, and not just in Britain.

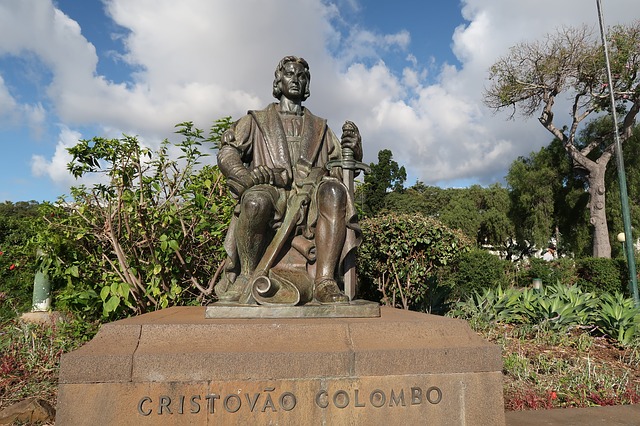

Protests in the US against Columbus Day have also gathered momentum. Parades have been cancelled, statues defaced and dismounted, and countless pieces written over the legitimacy of the celebration. Columbus’ crimes are more directly abhorrent than Colston’s, who profited from slavery. On his first voyage to the Caribbean, Columbus actually enslaved hundreds of indigenous people and brought them as gift to the queen of Spain. By 1509, including a period in which Columbus was governor of Santo Domingo (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), the native Taino population had been reduced from a mid-point estimate of 8 million, to just 100,000 and by 1542 only 200 remained. This genocide was the result of European disease, forced labour and slaughter that included the use of man-eating dogs. Columbus personally unleashed hell on earth on the Taino people and yet monuments, roads, universities and even cities in the United States (a country he never visited) bear his name to him. His adulation marked by public monuments is also common across Europe and I even remember reciting the famous rhyme ‘in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue’ in a primary school assembly. To commemorate Columbus is to celebrate genocide but there is little to no acknowledgment of this in mainstream discussions of his legacy.

Just as with Colston, the disturbing truth is that the worship of Columbus makes sense given the importance Europe ‘discovering’ America is to what we currently have. Genocide of the indigenous people in the region cleared the way for Europeans to migrate and dominate.

Without the Americas and Caribbean, there is no transatlantic slave trade in African flesh for Europe to engorge itself on for three centuries. Key commodities like sugar and cotton cannot be so cheaply procured, with the profits laying the foundation for the industrial revolution that powered European development. The Atlantic system was utterly essential to European progress and also fuelled the expansion of empire to other parts of the globe. Columbus is revered because he provided the opportunity (‘discovery’), means (genocide) and even pioneered one the key methods (slavery) for Europe to conquer the Americas, and dominate the globe.

We should not be remotely surprised that slave traders, genocidal murders and colonial despots represent a large amount of those heralded with monuments and public recognition in Britain. In order to build the nation (and the West as a whole) the pillage and plunder from Empire was indispensable. It is difficult to find a historical figure with no blood on their hands, and those who contributed the most to economic and political development often had the bloodiest. That is precisely why they are adored and honoured.

Any reasonable analysis of history would make us uncomfortably with lauding those who enriched themselves off, or were responsible for the death of countless innocent victims. But it is impossible for society to engage in such an analysis because once we reject people like Colston or Columbus we then need to question their legacies. Genocide, slavery and colonialism are some of the key building blocks for the very world (and comfort) we live in today. To question the legitimacy of historical folk heroes is to begin to interrogate our complicity in the unjust world they bequeathed us. The painful reality is that they cannot be excused as products of their time; our time is the product of their brutal endeavours.